As computer vision researchers, we believe that every pixel can tell a story. However, there seems to be a writer’s block settling into the field when it comes to dealing with large images. Large images are no longer rare—the cameras we carry in our pockets and those orbiting our planet snap pictures so big and detailed that they stretch our current best models and hardware to their breaking points when handling them. Generally, we face a quadratic increase in memory usage as a function of image size.

Today, we make one of two sub-optimal choices when handling large images: down-sampling or cropping. These two methods incur significant losses in the amount of information and context present in an image. We take another look at these approaches and introduce $x$T, a new framework to model large images end-to-end on contemporary GPUs while effectively aggregating global context with local details.

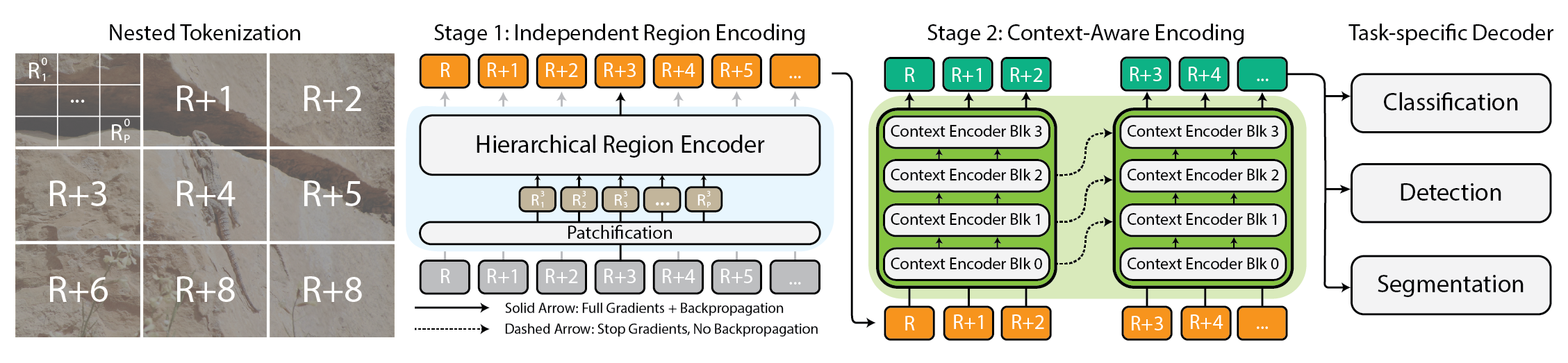

Architecture for the $x$T framework.

Why Bother with Big Images Anyway?

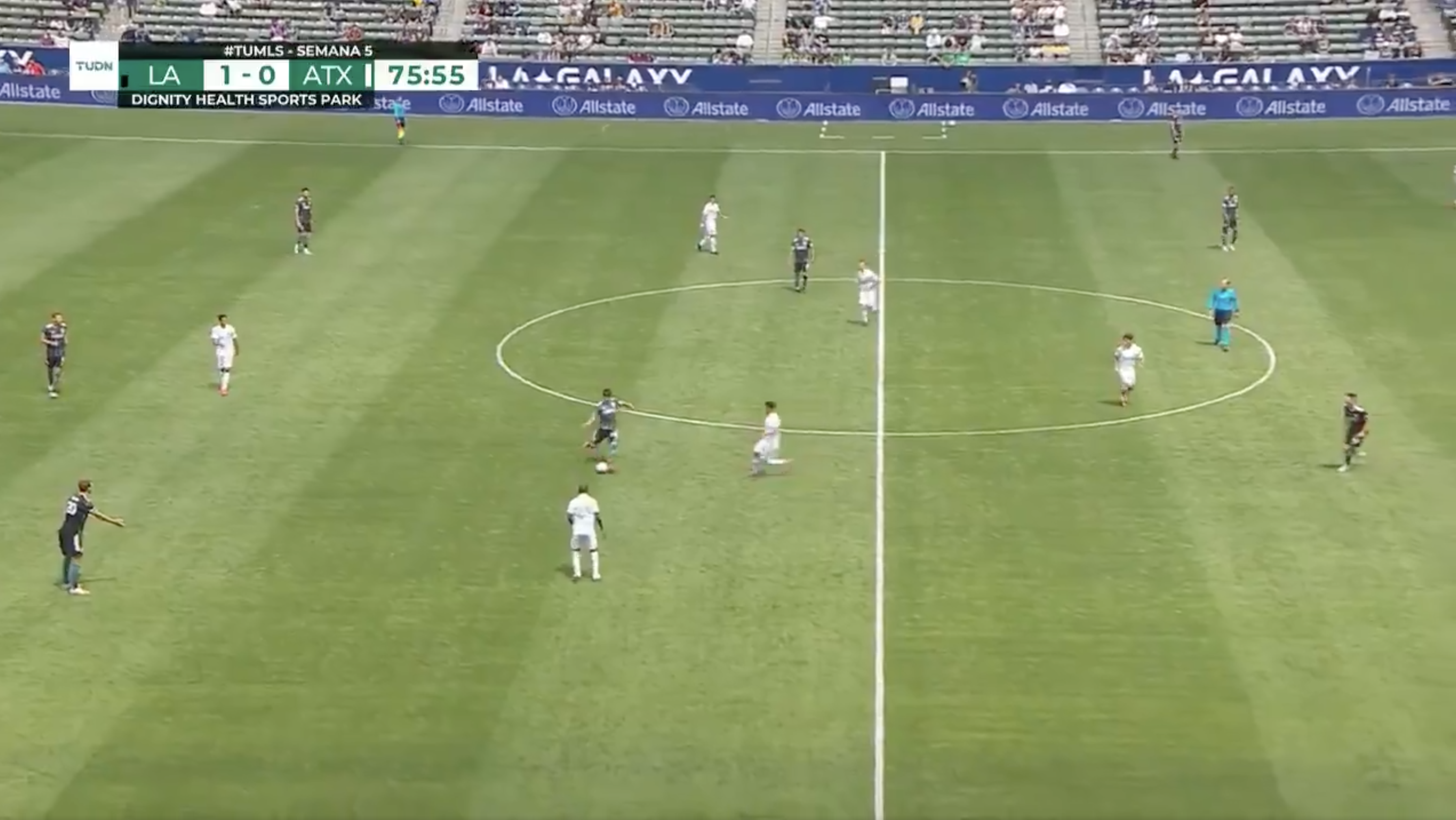

Why bother handling large images anyways? Picture yourself in front of your TV, watching your favorite football team. The field is dotted with players all over with action occurring only on a small portion of the screen at a time. Would you be satisified, however, if you could only see a small region around where the ball currently was? Alternatively, would you be satisified watching the game in low resolution? Every pixel tells a story, no matter how far apart they are. This is true in all domains from your TV screen to a pathologist viewing a gigapixel slide to diagnose tiny patches of cancer. These images are treasure troves of information. If we can’t fully explore the wealth because our tools can’t handle the map, what’s the point?

Sports are fun when you know what’s going on.

That’s precisely where the frustration lies today. The bigger the image, the more we need to simultaneously zoom out to see the whole picture and zoom in for the nitty-gritty details, making it a challenge to grasp both the forest and the trees simultaneously. Most current methods force a choice between losing sight of the forest or missing the trees, and neither option is great.

How $x$T Tries to Fix This

Imagine trying to solve a massive jigsaw puzzle. Instead of tackling the whole thing at once, which would be overwhelming, you start with smaller sections, get a good look at each piece, and then figure out how they fit into the bigger picture. That’s basically what we do with large images with $x$T.

$x$T takes these gigantic images and chops them into smaller, more digestible pieces hierarchically. This isn’t just about making things smaller, though. It’s about understanding each piece in its own right and then, using some clever techniques, figuring out how these pieces connect on a larger scale. It’s like having a conversation with each part of the image, learning its story, and then sharing those stories with the other parts to get the full narrative.

Nested Tokenization

At the core of $x$T lies the concept of nested tokenization. In simple terms, tokenization in the realm of computer vision is akin to chopping up an image into pieces (tokens) that a model can digest and analyze. However, $x$T takes this a step further by introducing a hierarchy into the process—hence, nested.

Imagine you’re tasked with analyzing a detailed city map. Instead of trying to take in the entire map at once, you break it down into districts, then neighborhoods within those districts, and finally, streets within those neighborhoods. This hierarchical breakdown makes it easier to manage and understand the details of the map while keeping track of where everything fits in the larger picture. That’s the essence of nested tokenization—we split an image into regions, each which can be split into further sub-regions depending on the input size expected by a vision backbone (what we call a region encoder), before being patchified to be processed by that region encoder. This nested approach allows us to extract features at different scales on a local level.

Coordinating Region and Context Encoders

Once an image is neatly divided into tokens, $x$T employs two types of encoders to make sense of these pieces: the region encoder and the context encoder. Each plays a distinct role in piecing together the image’s full story.

The region encoder is a standalone “local expert” which converts independent regions into detailed representations. However, since each region is processed in isolation, no information is shared across the image at large. The region encoder can be any state-of-the-art vision backbone. In our experiments we have utilized hierarchical vision transformers such as Swin and Hiera and also CNNs such as ConvNeXt!

Enter the context encoder, the big-picture guru. Its job is to take the detailed representations from the region encoders and stitch them together, ensuring that the insights from one token are considered in the context of the others. The context encoder is generally a long-sequence model. We experiment with Transformer-XL (and our variant of it called Hyper) and Mamba, though you could use Longformer and other new advances in this area. Even though these long-sequence models are generally made for language, we demonstrate that it is possible to use them effectively for vision tasks.

The magic of $x$T is in how these components—the nested tokenization, region encoders, and context encoders—come together. By first breaking down the image into manageable pieces and then systematically analyzing these pieces both in isolation and in conjunction, $x$T manages to maintain the fidelity of the original image’s details while also integrating long-distance context the overarching context while fitting massive images, end-to-end, on contemporary GPUs.

Results

We evaluate $x$T on challenging benchmark tasks that span well-established computer vision baselines to rigorous large image tasks. Particularly, we experiment with iNaturalist 2018 for fine-grained species classification, xView3-SAR for context-dependent segmentation, and MS-COCO for detection.

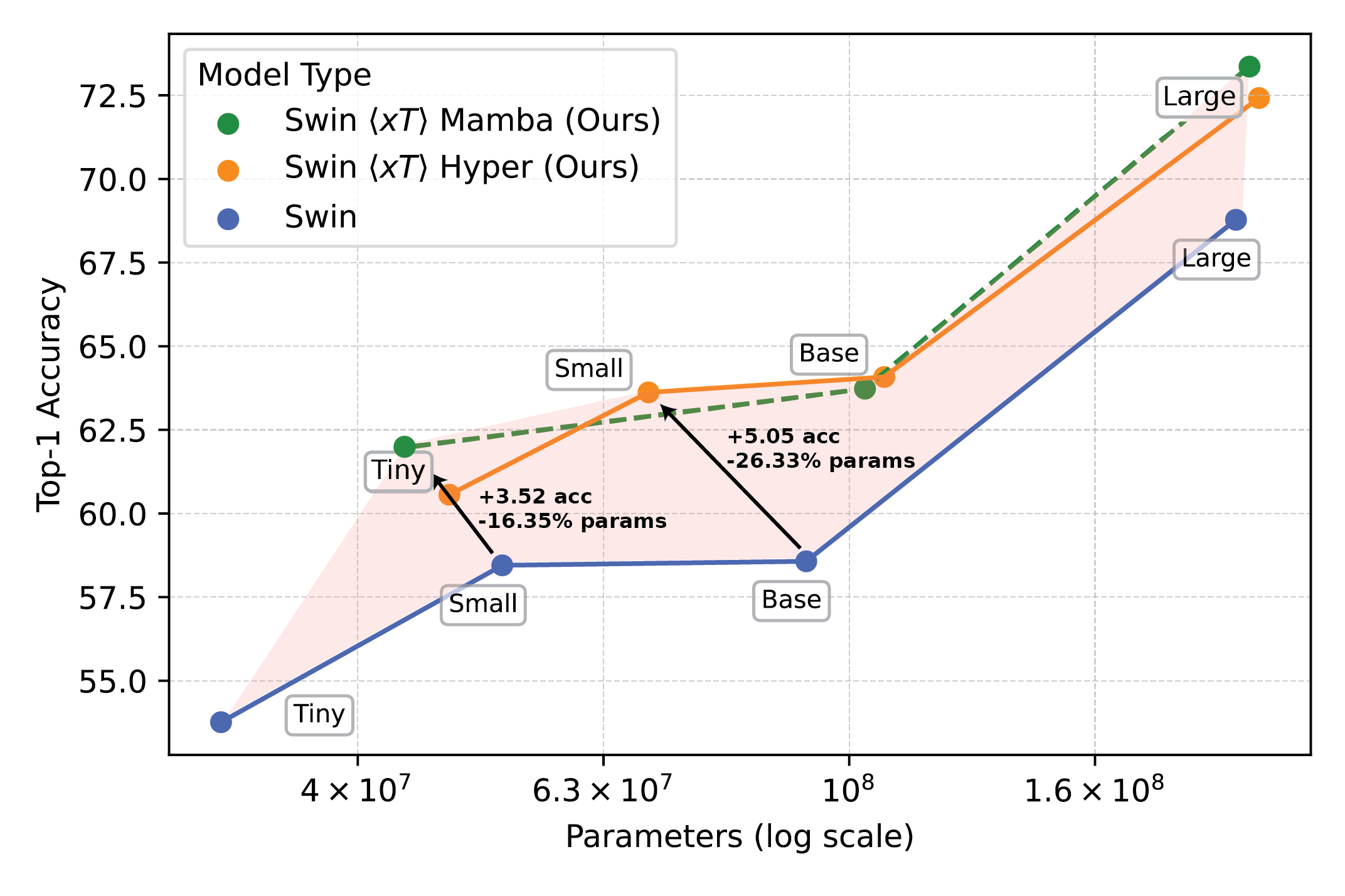

Powerful vision models used with $x$T set a new frontier on downstream tasks such as fine-grained species classification.

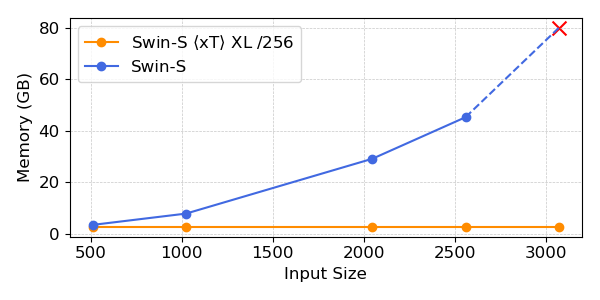

Our experiments show that $x$T can achieve higher accuracy on all downstream tasks with fewer parameters while using much less memory per region than state-of-the-art baselines*. We are able to model images as large as 29,000 x 25,000 pixels large on 40GB A100s while comparable baselines run out of memory at only 2,800 x 2,800 pixels.

Powerful vision models used with $x$T set a new frontier on downstream tasks such as fine-grained species classification.

*Depending on your choice of context model, such as Transformer-XL.

Why This Matters More Than You Think

This approach isn’t just cool; it’s necessary. For scientists tracking climate change or doctors diagnosing diseases, it’s a game-changer. It means creating models which understand the full story, not just bits and pieces. In environmental monitoring, for example, being able to see both the broader changes over vast landscapes and the details of specific areas can help in understanding the bigger picture of climate impact. In healthcare, it could mean the difference between catching a disease early or not.

We are not claiming to have solved all the world’s problems in one go. We are hoping that with $x$T we have opened the door to what’s possible. We’re stepping into a new era where we don’t have to compromise on the clarity or breadth of our vision. $x$T is our big leap towards models that can juggle the intricacies of large-scale images without breaking a sweat.

There’s a lot more ground to cover. Research will evolve, and hopefully, so will our ability to process even bigger and more complex images. In fact, we are working on follow-ons to $x$T which will expand this frontier further.

In Conclusion

For a complete treatment of this work, please check out the paper on arXiv. The project page contains a link to our released code and weights. If you find the work useful, please cite it as below:

@article{xTLargeImageModeling,

title={xT: Nested Tokenization for Larger Context in Large Images},

author={Gupta, Ritwik and Li, Shufan and Zhu, Tyler and Malik, Jitendra and Darrell, Trevor and Mangalam, Karttikeya},

journal={arXiv preprint arXiv:2403.01915},

year={2024}

}

Source: http://bair.berkeley.edu/blog/2024/03/21/xt/